by Kostas Konstantinidis

“The musician, like music, is ambiguous. He plays a double game. He is simultaneously musicus and cantor, reproducer and prophet. If an outcast, he sees society in a political light. If accepted, he is its historian, the reflection of its deepest values. He speaks of society and he speaks against it. This duality was already present before capital arrived to impose its own rules and prohibitions.”

Jacques Attali – Noise: The political economy of music

Since 1899 and his seminal work Conspicuous Consumption, Τh. Veblen states that a social class, that exists already from pre-neoteric age, demonstrates its wealth and prosperity, both material and non-material, and lives on the expense of others, by promoting a life based on leisure time. His critical approach confronts the Second Industrial Revolution and a bourgeois class of newly rich individuals that emerged from it and tended not to just take pleasure from objects and services that were available, but use them as trophies of its social status. By observing the results of the provision of services industry and the up and coming leisure class of “influencers” one cannot but feel rather pessimistic about the persistence of such practices which seem to remain unchanged. Wealth is still not only a matter of just materials and objects but it is embodied by the influencers in beauty standards and leisure time gets to be a commodity, since its commercial use aspires to be a matter of jealousy for the less fortunate people. This way, the latter fantasize about living a life of a person that constantly travels to exotic locations, but themselves seem trapped in an unbearable everyday life.

The Age of Extremes, the 20th Century, an epoch of disenchantment for the romantic capitalism of Belle Epoque, an age in which Veblen lived, and the total domination of Neo-liberalism in the bigger part of the western world after WWII, couldn’t but be a prominent domain for the newly rich and for conspicuous consumption, since the plethora of offered goods and services made it rather easy. The rise of a counterculture during the 60’s, confronted artists with a dominant pop culture and its colonization by an American oriented market of cultural goods, conservative and shallow, ideal for a fast-food like consumption which took place in a rather tired and no less equally conservative post-WWII world, who was engaged in a Cold-War reality without being able to recover its strength.

Consuming goods was slowly evolved in some kind of psychological relief but also in a pivotal factor of social identity formation. Counterculture and her branches, like was later labeled as prog rock, couldn’t be uninterested towards such phenomenon. Even though there exists a misconception that Progressive Rock is an ars gratia artis apolitical genre, based solely on musical experimentation rather than social commentary, this article aims to prove that things are not exactly like that. And things couldn’t have been like that, since artists are not detached from the political and social context of their time, they are not without interest for everything that’s happening around them and even by using allegorical and abstract, sometimes cryptic, meanings, they try to adapt in their works of art everything that considers them as citizens. With two well-known songs, Dancing With The Moonlit Knight by Genesis and Heresy by Rush, the lyricists, Peter Gabriel and Neil Peart respectively, comment on consumerism, a sociopolitical matter, and despite their common petit-bourgeois origins, they approach it very differently. So is prog rock as apolitical as it is thought to be? To examine progressive rock and its ambassadors in that context, we shall travel to its birthplace, which is the South-East of England, the area with the largest, now and then, per capita income in the country, and, in the case of Rush, the typical bourgeois suburban neighborhood. We will try to get a better hold of their political views, and the already known lyrics will shed light to other meanings, viewed from a sociopolitical and historical point. Lastly, we will talk about one’s right to criticize and if this kind of conversation is useful for music lovers and afficionados.

Can u tell me where my country lies? The anthropogeography of early prog rock

In the map below we noted the birthplaces of most of the 100 most popular progressive rock artists as they are ranked according to the members of progarchives.com, perhaps the most well-known webpage dedicated to the genre. The choice was made for practical reasons of course, because this list contains most of the pioneers of the genre and it also proves that the geographical area of its birthplace is indeed the South-East of England, despite its future diffusion in the rest of the world and its prominence and popularity during the 1970’s.

Many of the genre’s pioneers, maybe most of them, come from a middle-class environment, which in England is perceived as white collar as in contrast with the blue collar working class. For example, Robert Wyatt, who was born in Bristol and raised in Kent, had a mother that came from a well-off family and worked for BBC, while his father was a psychologist. In the idyllic countryside of Kent, his parents, although they adopted a bohemian lifestyle by denying their inherited family wealth, they rented a mansion with several rooms, which they rented to students and artists for income. In one of these rooms resided, rumor has it, Daevid Allen, an newcomer in Britain from Australia. His acquaintance with Wyatt would be seminal for what in the future came to be known as Canterbury Sound, one of the most distinct and sui generis subgenres of prog rock. Wyatt himself denies the existence of such a “sound” but that’s a whole different story…

Another significant individual, also residing in the area, was Kevin Ayers, a son of an also bourgeois family, with his father being a poet and BBC producer and his future stepfather a diplomatic civil servant who was appointed in Malaysia, where Ayers spent his adolescence, up to the age of 12. Peter Gabriel, born in Surrey, was even more privileged, since his family managed to ensure that he would get a high-profile education in general and in music specifically, by enrolling him to Charterhouse Public School, one of the most prestigious Schools in the country at the time, in which he met Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford and Christ Stewart, and formed the core of what became Genesis. We can see similarities in the case of Pink Floyd, because Roger Water, Nick Mason and Richard Wright met at Regent Street Polytechnic, being students in the faculty of Architecture.

According to Edward Macan and his book Rocking the Classics: English Progressive rock and the counterculture, Anglican Church’s influences in the southern regions of the country was another factor that played a crucial part in the overall forming of prog rock. Canterbury and its medieval Cathedral is the head of Anglican Church and a place of pilgrimage, in a country that isn’t famous for being overly religious. Nevertheless, many of prog rock pioneers came in touch with the rich choral and musical tradition of the church during their school years and many of them used choirs in their compositions. Chris Squire of Yes was a member of a church choir, while Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine studied church organ in Canterbury Cathedral.

This influence was significant for the evolution of the genre, perhaps in the same manner that the rock n roll musicians based, form wise, on the Blues. The re-discovery of religious musical tradition of black people by the baby-boom generation gave to the newborn rock n roll a spiritual identity and defined its revolution. The intensity and the emotional charge of the blues, a tug-o-war between joy and despair, gives an almost ecstatic character to the sound and a rhythmic impulse that is embodied through dancing. It is common ground when we bring in mind scenes where the whole of the congregation is dancing and singing. Rock n roll borrowed that inner spiritual impulse and made it even louder by adding a sexual-Dionysian aspect. Prog rock on the other hand followed on the steps of this transcendental spiritual heritage of ecclesiastical music, brought elements from classical music, but it could not comply with their limitations. As a style, it kept the heritage of its geographical roots and the high-profile aesthetics that it adopted inside colleges and universities, but in the meantime it deviated through elements of jazz, atonal music, psychedelia, contemporary classical music which found their place in the genre’s typical lengthy and adventurous musical compositions.

On the other side of the pond, in Canada as the birthplace of Rush, we also have common class origins, but a different social evolution in the suffocating everyday life of the suburbs, which Neil Peart rebuked so intensely in his lyrics. Canada as a country played a secondary role in the Cold War and also in the developments in pop culture and counterculture that blossomed in the USA and in Britain. Prominent Canadian artists, such as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, can be found at the time in Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles, the epicenter of counterculture. Peart himself describes an idyllic childhood in the suburbs of St. Catharines and his strolls along Lakeside Park found their place in his lyrics in the song with the same name, as nostalgic reminisces. In his book Travelling Music he mentions the almost classless environment in which he grew up, even though he recognizes that there were less privileged children and other wealthier families. In that sense he considered his own family as middle-class. He portrays his education as a blend between American and British and testifies that even as a child he wasn’t able to stay unaffected by the whole Cold War atmosphere of the time and the constant threat of the imminent USSR invasion to the Western World. The sorrow and empathy of the Canadians for the JFK assassination, the duck & cover films that were screened at schools, the Cuban missile crisis and the fear of nuclear disaster had an impact in the way children were psychologically traumatized by the events and, in the big picture, the heteronomy of Canada, who was bounded culturally and politically by the politics of USA and Britain.

Besides the bourgeois origins, both lyricists grew up inside a racial and cultural homogenous environment. Peart writes that he did not meet any person of color until he became a teenager. Same in SE England where there is not much diversity in ethnicity, since 85% of the residents are white British as the image below shows clearly.

Hare Hare Supermarket

Even though these two songs are not the only ones that the two lyricists tackle consumerism as a subject, Dancing with the Moonlit Knight and Heresy are very distinctive and they showcase the opposite views on the same matter, despite their common social origins. In the case of Genesis, Dancing with the Moonlit Knight is one of the most well-known songs, in one of their most iconic records, Selling England by the Pound. In the case of Rush, Roll the Bones is not considered one of their best records, but it came out almost at the same time as the collapse of the Soviet Union and thus Peart’s commenting, with him being a brilliant lyricist, is a valuable and interesting contemporary source.

In Dancing with the Moonlit Knight Peter Gabriel addresses to the listener as an incarnation of the Soul of Britain. Let’s not forget that he used to come on stage dressed and presented himself as Britannia. Before he starts mocking consuming mania, he sets allegorically but at the same time a realistic reality of abundance, which provokes citizens to consume and reach happiness.

With repeated wordplay even from the start of the song we are transferred in the realm of myth, with unifauns (wordplay for a non-existent creature, even in the fantasy realm. Probably something between a unicorn and a faun, that also sounds like “uniform” and maybe he means someone wearing such) and also the Queen of May (be), the goddess of abundance, Spring and the hope for a good harvest, similar with the deity Demetra from the Greek Pantheon.

Father Thames is another mythical entity, who as a river, is a bringer of life and prosper in the city and the country. He becomes one more icon of abundance and a nostalgic, romantic and not so realistic, but idealistic representation of a pre-neoteric economy, that was lost forever and was replaced by a capitalist economy and a new generation that consumes constantly. When the Old Man in the song dies, the old generation which proclaimed that “you are what you eat, eat well”, the new generation comes, the Young Man, who as it seems does not share the same views and values and believes that “you are what you wear, wear well”. The change in priorities is obvious and for Gabriel the new generation of the baby-boom, consumes more superficially.

This kind of abundance was still present at the post war era, which came as a surprise after all the bombings and whole cities in ruins. According to historian Ian Kershaw, Britain managed to incorporate immigrants as cheap workers, which gave boost to the economy. Things changed radically during the 70’s and that’s why Old Father Thames signs the letter of the bygone old generation, the one that lived in a state of abundance. Gabriel as a social commentator couldn’t be uninterested in the situation around him. “Selling England by the Pound” is rumored to be a motto of the Labour Party at the time. Crisis was already evident and it didn’t take long to show its teeth. Oil crisis in 1973, as a result of the Arab-Israeli war, launched inflation and unemployment in England and the powerful Empire was considered the new “sick man of Europe”.

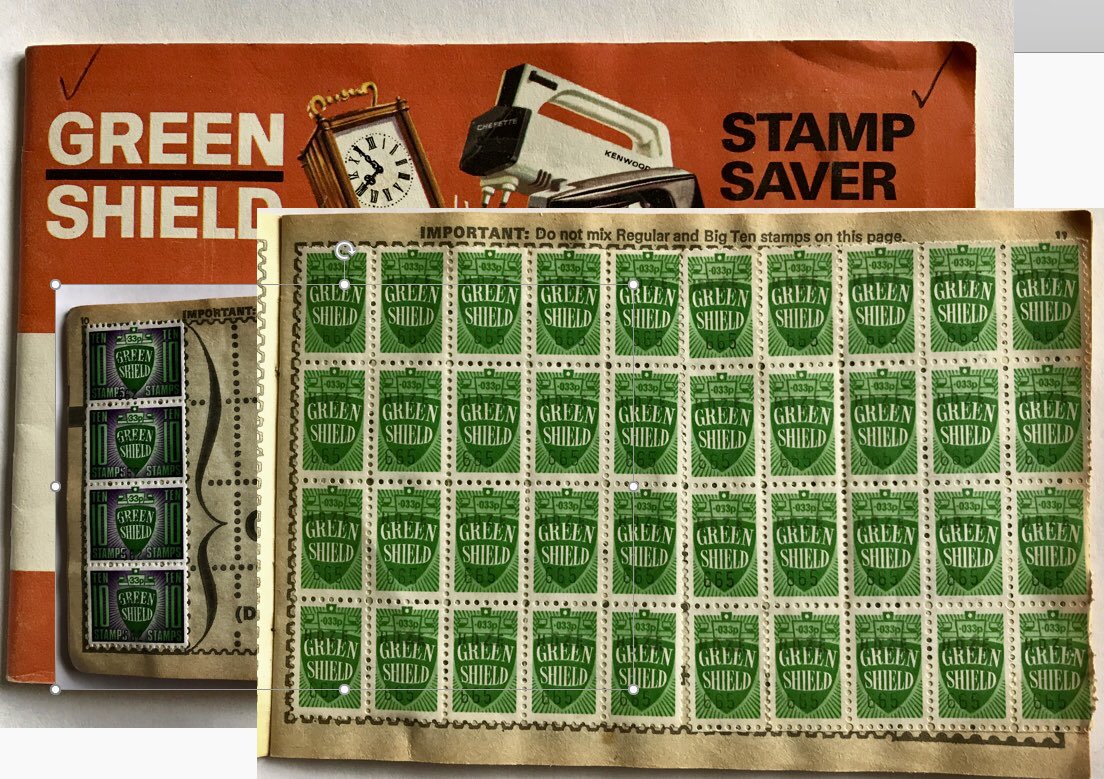

The constant shifts between myth and reality are continued in the song, with consumerism being the target of Gabriel’s phlegmatic irony. The Arthurian Cycle is introduced by the mentioning of the Holy Grail and the Knights of the Round Table, coming to an end with the probably most tongue-in-cheek lyric of the song, with the consumers being described as Arthurian knights, shouting with joy after collecting the discount green coupons/stamps (also a parody of the Medieval folktale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The citizens of Britain, (the citizens of hope and glory as they are named by the patriotic song Land of Hope and Glory, sung by Vera Lynn amongst others) are once again portrayed to literally consume their bourgeois dreams. These dreams Gabriel calls them Wimpey, a double wordplay once again, coming from Wimpy, a fast-food chain brand of the era and also Wimpey housing company, which used to build cheap and identical houses during the post-war to solve the housing problem.

A kind of supernatural aspect of consuming is overstated with the “fat old lady” of the song, a stereotypical and dismissive Anglo-Saxon expression for the often obese opera primadonnas that used to sing before the curtain falls, like the character of Brunhilda in the Wagnerian Ring of Nibelungen. That lady in Dancing… rather than having Tarot cards to tell the future, she foresees it with the help of credit cards, a method of payment that in the 70’s was taking its first steps and a must-have object for establishing the owner’s financial status. In Aisle of Plenty, the finale of the album and a complement to Dancing with the Moonlit Knight there are further mentions to supermarket chains with clever wordplay by Gabriel, like Fine Fare and Tesco, discount shops, and it also includes a price list of various products. The ultimate completion of the consumer on this island of plenty (of abundance) meaning both the supermarket aisle and the island of England, comes with the phrase “its scrambled eggs”, which in British slang, according to the slang dictionary, means awarding a military man with a medal, which corresponds excellently with the rewarding of the consumer with a discount stamp, a green shield or such.

Back in the USSR…

In Heresy on the contrary, consuming goods is presented and identified as the essence of freedom by Peart. In the opposite side of Gabriel’s allegorical and coded wordplay, Peart is totally clear in what he wishes to say and his political beliefs.

“All around that dull gray world

Of ideology

People storm the marketplace

And buy up fantasy

The counter-revolution

At the counter of a store

People buy the things they want

And borrow for a little more

All those wasted years”.

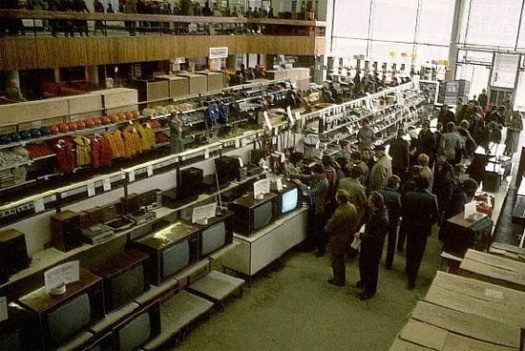

Consumerism in shops and supermarkets is presented as a revolutionary act, against the October Revolution and the communist regime. He thinks of banking loans and credit cards as means of self-liberation, because, as he specifically writes, one can “buy up fantasy” with them. In the Roll the Bones tour book he further explains his feelings and states that after the Wall fell and USSR collapsed he felt mad, because for “generations those people had to line up for toilet paper, wear bad suits, drive nasty cars and drink bug spray to get high – and it was all a mistake? A heavy price to pay for somebody else’s misguided ideology, it seems to me, and that waste of life must be the ultimate heresy”.

Nobel Prize laurate Svetlana Alexievich in her book Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets shares with us an aftermath testimony of the everyday life in the Eastern Block, so it is interesting how those people managed to cope with the lacking of goods and the post 1989 western world capitalist consuming way of life and finally what freedom meant for them.

“So here it is, freedom! Is it everything we hoped it would be? We were prepared to die for our ideals. […] Now we have new dreams: building a house, buying a decent car, planting gooseberries… Freedom turned out to mean the rehabilitation of bourgeois existence […], The freedom of Her Highness Consumption. Darkness exalted. The darkness of desire and instinct—the mysterious human life, of which we only ever had approximate notions. […] here are thousands of newly available feelings, moods, and responses. Everything around us has been transformed: the billboards, the clothing, the money, the flag…And the people themselves. They’re more colorful now, more individualized; the monolith has been shattered and life has splintered into a million little fragments, cells and atoms. […] no one was talking about ideas anymore—instead, it was credit, interest, and promissory notes; people no longer earned money. They “made” it or “scored” it.

I asked everyone I met what “freedom” meant. Fathers and children had very different answers. Those who were born in the USSR and those born after its collapse do not share a common experience—it’s like they’re from different planets. For the fathers, freedom is the absence of fear. A man with his choice of a hundred kinds of salami is freer than one who only has ten to choose from. […] For the children: Freedom is love; inner freedom is an absolute value.”

So, Peart wasn’t wrong about the desires and their pursuits of the “sovok”, as the nostalgists of the Soviet Union are called. Queues did exist, as did lack of certain goods, but there also was a big difference between the volume of the poverty and the shortage of supplies depending in which country you lived, which area and what decade. Huge lines of people waiting for a meal and extreme poverty is not a USSR only phenomenon, it still happens today in capitalist countries and manihaistic approaches do not shed light to what’s really happening but they rather reproduce Cold-War stereotypes. What matters in USSR’s case is if the new capitalist reality verified their expectations. From what Alexievich writes that doesn’t seem to have happened, at least not as much as they expected to:

“The living is better. And for some people, it’s gotten a thousand times better. I’m fifty years old… I try not to be a sovok, but I’m not very good at it. I work at a private company and hate the owner. The way they split up the big pie of the USSR, their pirate privatization, just doesn’t sit well with me. I don’t like the rich. They’re always showing off their palaces on TV, their wine cellars… They can bathe in breast milk in gold bathtubs for all I care! What do I need to see that for? […] I lived under socialism for too long. Life is better now, but it’s also more revolting.”

Veblen’s observations on conspicuous consumption of the newly rich and the new oligarchy that was risen from the ashes of the USSR are confirmed and up to now wealth is still amassed in the hands of the few, with intense class separation. Putin’s government of course tries to utilize the former military victories of the Great Patriotic War for moral compensation of the people through patriotic and nationalist rhetoric, because Russians still see their expectations for a better life to be disproved. So, it does not come as a surprise when Josef Stalin appears to be the most popular person in history, in a respective public vote, followed of course by Vladimir Putin. During the Photobiennale 2018-2019 in Thessaloniki’s Museum of Photography, German photographer Anna Skladmann exhibited a series of photographs called Little Adults and were about the visualization of everyday life of Russia’s financial elite’s children. The message was that child innocence was lost because of the conspicuous luxury and the controversial aesthetics of the newly-rich. There were photographs of little boys carrying AK-47s in their bedrooms or little girls, with make-up and adult clothes, posing in their “little” private theater inside their house. Consumption becomes an end in itself, a self-fulfillment situation and at the same time a show off of power and social status. The meaning of freedom is once again under revision, and still, according what Peart believed about the USSR, we have a “heretic” behavior of authority, this time inside the capitalistic world-system. Why is Peart so different from Gabriel on the same subject?

Neil Peart, already from a young age and being a book-worm, delves deeply inside the world of Ayn Rand. The neoliberal ideology in her writings is intense and she also adopts a profound conservatism that was against to any kind of counterculture and sexual freedom. She also shows a religious like commitment to the values of personal initiative and ingeniousness, when she presents the individual as a self-luminous entity, cut out completely from the rest of the society. This spirit of individualism is present in many songs that Peart wrote lyrics for, and like Gabriel, he resides in myth and allegory to unfold his ideas. He dedicates the whole album 2112 to the “genius of Ayn Rand”. In songs like The Trees he confesses his faith in a congenital genius superiority that must not be contained by the will of the many, which holds back the creative force of the “excellent” and also that perfect equality is impossible, except in death. In Hemispheres, where he presents the classic philosophical and mythological dipole of Apollo and Dionysus, of Reason and Emotion, he seems to deviate from the totally amoralistic psyche of Rand’s characters and embraces the hedonism of the Woodstock generation, whom Rand seemed to despise. By that he already shows the first signs of a transition, from a preacher of individualism to a poet who celebrates human nature as a whole, without renouncing his optimism for a constant progress through individual genius and also his concerns about the dark side of humans. These concerns show themselves as latent pessimism in the finale of songs like The Trees where all trees are chopped down by the lumberjack and in Cygnus X-1 where the Don Quixote of a hero flies his Rosinante inside a black hole.

It would be unfair for Peart’s influential lyrics, if only this side of it was referenced. Like Gabriel, during the next decades, he put aside the mythological, literature and allegorical themes and they’ve both introduced a body of work full of realistic concerns and head-on lyrics. Thus, Gabriel, from an admirer and student of T.S. Elliot’s poetry and from stories about the nymph-Naiad Salmacis becomes intensely critical on the apartheid, while Peart respectively, from the Fountain of Lamneth and the myths of Dionysus will be transformed in an erudite and well-travelled intellectual who will even comment on social inequalities in The Larger Bowl. In one of his interviews, in 2012 in Rolling Stone magazine, he will denounce his obsession with Ayn Rand’s philosophy and he will declare himself a “bleeding heart libertarian”(he formerly declared “left wing libertarian”). Rush as a band, as they stated in interviews, confess that they did not think of themselves being politicized back then and they did not embrace fully neoliberal ideology. On the contrary the lyrics mainly refer to youth skepticism, work ethic and to the belief that an individual can change the world around him.

They both pursue the meaning of consumerism in confided geographical space. In the case of Genesis, the space is of course England, where Gabriel criticizes the consuming habits of his co-citizens, with no intent to globalize his ideas. In Selling England by the Pound we can find many mentions in actual places like the Epping Forest or the Firth of Forth in Edinburgh, which becomes Firth of Fifth in the record. In Heresy ex-USSR and the Eastern Block become the setting, which are described as “that dull gray world from Moscow to Berlin, People storm the barricades,Walls go tumbling in”, thus reproducing the stereotypical views that were imposed in the way Westerners perceived what was happening behind the Iron Curtain. So Peart on the contrary tries to give a global aspect of freedom, with capitalistic consumerism as its pinnacle and being on the opposite side of lack of goods and consequently giving to freedom, a pluralistic term, a one sided meaning. This grey and dull reality is not something radical in western pop culture, which took an active role during the Cold War and was used and abused for propaganda reasons, even by secret services, like the example of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago, which was used by the CIA as an anti-communist tool.

Tales from Apolitical Oceans

Despite the social critique and the political views of the artists prog rock has more or less perceived as a mainly apolitical genre, a sui generis subculture which operated within the confines of the counterculture of the time, by giving to the listeners a different spectrum of stimuli. From a structural aspect the original British version of prog rock was not so much based on psychedelia but rather on jazz and classical music, without denouncing the Beatle’s legacy nevertheless. That makes prog rock a highly eclectic genre, which tries to include different influences. By the end of the 60’s the single format was replaced by LP records and artists had more space and time to fill with their ideas. That alone gave artistic freedom and creativity exploded, which through certain social aspects gave birth to progressive rock.

How did the youth of the era react towards the allegorical and mythological lyrical adventures?

Probably they did pay no attention at all, like many nowadays don’t. And if they did, it was not the same attention that Dylan’s or Baez’s lyrics drew. Maybe they were more impressed by the virtuosity and the original sounds that they heard- probably totally stoned- in their cheap portable turntable. Besides a small minority of higher educated listeners, they wouldn’t bother to analyze the subtle irony in Gabriel’s lyrics. The only thing for sure is that many music critics did not admire the Ayn Rand influences in Rush and their philosophical endeavors about individualism, so some of them went that far as to label them fascists. Until that point in time, in the mid-70’s, there was a disenchantment of all the dreams that the Woodstock generation had, and progressive rock, as time passed, became more and more self-referential. The artists themselves were evolved and progressed, their style changed, their popularity rose and the music business demands likewise. The concerns of youth counterculture in the end of the 60s and the early 70s were replaced by a more apolitical and more complied version of prog rock, which during the following decades, the 80’s and the 90s, will lose its radicality, musical and lyric wise. Just to be fair, for many of prog rock’s subgenres, the will for experimentation and for political expression did not cease to exist, but it was displaced geographically in countries like Germany or Italy, far from its birthplace on British soil.

Artists create in a certain sociopolitical frame and they can’t help but express the spirit of the age, their origins, their sensibilities, a part of themselves. Even if a work of art seem ahead of its time, this mainly stems from a future analysis, which projects on it the apperceptions and the needs of the contextual present. For certain, there is no credibility in the argument that it couldn’t be understood by the people of its time. The ever persistent myth of the genius that acts alone, away from its social context, remains a rather convenient narrative that easily explains some things, but we must bear in mind that even the brightest individuals were inspired and contributed to their societies, without necessarily thinking about their legacy and the way that people of the future would appreciate their work. Thus, this totemization of a work of art as “classic”, and by that placing it in a place above any kind of criticism, probably does harm and is unfair to the work of art itself.

Bands like early King Crimson, Henry Cow, Matching Mole, Jethro Tull, Area and Van Der Graaf Generator were more or less political and debunked the common conception about the apolitical side of progressive rock. Of course artists like Υes, with their sophisticated and rather cryptic lyrics, because of their popularity, cause such stereotypes and associations. But even there, one can discern the ecological, pacifist and social concerns the band has, inside this otherworldly, utopian and positive aesthetics. Subsequent artists like Marillion don’t hesitate to create in a similar sociopolitical framework but the majority of later artists (like Neal Morse or The Flower Kings) seems to prefer more metaphysical, new age, philosophical and religious themes.

The question remains, if all of these analyses, like the case of consumerism, are necessary or someone should stick to the aesthetic pleasure and not talk about all these, which may concern even fewer people than prog as a relic of the “dinosaur age of music” concern anyway. The answer can’t be yes or no and it relies not only in the expectations of the listener but also in mood, time, concerns, ideology and many more aspects. Problem is that by delving deeper and by analyzing the ideological origins of the artists one can be confronted with awkward situations, especially when the artist and the work of art are coincided and the messages that they pass onto the listener have a very clear and particular ideology behind them. This became evident in cases where artists flirted with fascism for example. Sometimes the receiver, by consuming a work of art reaches a dilemma in which no decision has a positive outcome. So either the work of art ends as a ideologically discharged entity and is received with aesthetical and moral criteria of the present time, which can lead to anachronisms and cancel culture anathemas or it gains a classic status and is put on a stall, as an amoralistic product of an artistic genius, which as an exhibit, as a milestone, is beyond criticism (aesthetic or otherwise) and we end also in anathemas, this time of everyone who dares not recognize its value. But who gave this value and with what criteria is often not mentioned or is accredited to an almost metaphysical dedication to some indefinable “common taste”, holding the same value as “common sense”, which is no value at all.

On the opposite side, artists themselves, when they are being cut away from their cultural context, are idealized and the expectations that society has from their actions become greater, because they are assigned, unintentionally, with a certain role that they must constantly prove themselves that they are up to the task. At the same time we observe the reproduction of a moralizing aspect of their work, and because of it, their actions and their lives in general must be conformed with the high art they create. This practice leads to a vicious cycle and the aforementioned anathemas. Art itself is fetishized, and that’s why it is bought and sold as commodity, without any projected ideology on it, by having a certain price, which is defined by its rarity and the weariness that time brought on it, thus with criteria that have nothing to do with its aesthetic value, nor the artist or its content. The conversations which emerge are both about the relation between the artist and the work of art and also collecting art as a consuming-capitalistic mentality. So, it doesn’t really matter if this kind of approach puts artists’ value in stake or about the will to be iconoclastic for the sake of it, but the right to be critical towards a “sacred cow” of Art and the potential to scrutinize parameters that often escape public awareness intentionally or not. We owe to make clear that aspects of the artists mentality that will lead to moralizing judgements and paternalistic conclusions do not present any real interest, since they have nothing to do with their work, recorded or not. What really matters is that artists, live, breathe and create inside a social, cultural and political frame and even if they try to exercise their art in an artificially isolated environment or self-exile, this influence cannot be helped but being reflected in their work.

This kind of analysis, for reasons of saving space and time, is not practical to be applied in every record that is released and the repetition of the same conclusions is rather meaningless, because they don’t add something useful. On the other hand, there come new views and aspects that were not taken under consideration by the consumers, and why not, by the reviewers themselves. It goes without saying that no matter what ideology someone has the aesthetic pleasure that stems from listening the album is the main concern, so it is unnecessary to set the question if it’s ok for a left wing to listen to Rush or a conservative to listen to Bruce Springsteen or Rage Against The Machine. Also pointless is the conversation about whether the artists themselves are consistent to what they believed 10-20-50 years ago, since stagnation equals artistic regression with rather dated results. We all tend to evolve, progress, change, mature (..or not), and we get to comply more or less and adapt to the current situations, unless we decide to follow on Christopher McCandless steps in Into the Wild and try to live liberated from the restraints of consuming and social conventions, with hoping not having the same ending as him. Artists act alike. It’s scrambled eggs.

References

Αλεξίεβιτς, Σβετλάνα, Το τέλος του κόκκινου ανθρώπου, μτφ. Αλεξάνδρα Δ. Ιωαννίδου, εκδόσεις Πατάκη, Αθήνα, 2016.

Attali, Jacques, Noise: The political economy of music, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis-London, 2009.

Filipov, David, “For Russians, Stalin is the ‘most outstanding’ figure in world history, followed by Putin”, Washington Post, 26/6/2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/06/26/for-russians-stalin-is-the-most-outstanding-figure-in-world-history-putin-is-next/, (πρόσβαση 4/3/2021).

Hegarty P., Halliwell M., Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock since the 1960s, Continuum International Publishing Books, New York-London, 2011.

Johnes, Martin “Consuming Popular Music: Individualism,,Politics and Progressive Rock”, Cultural and Social History, 15:1, 115-134, 2018 DOI:10.1080/14780038.2018.1426815

Kershaw, Ian, Η Ευρώπη σε δίνη (1950-2017), μτφ Μενέλαος Αστερίου, εκδ. Αλεξάνδρεια, 2020

Macan, Edward. Rocking the Classics, English Progressive Rock and the counterculture, Oxford University Press, Oxford-New York, 1997.

Μason, Nick, Inside Out: A personal history of Pink Floyd, Weidenfeld&Nicolson, London, 2004.

Peart, Neil, Travelling Music: the soundtrack to my life and times, ECW press, Toronto,Ontario, Canada, 2004.

Peart, Neil, “Neil Peart on Rush’s New LP and Being a ‘Bleeding Heart Libertarian’, συνέντευξη στον Andy Green, Rolling Stone, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/neil-peart-rush-new-lp-248712/, 12/6/2012, (πρόσβαση 3/3/2021)

Πετσίνη, Πηνελόπη et al, Capitalist Realism : συντελεσμένο μέλλον-παρελθόν διαρκείας, Εκδόσεις Πανεπιστημίου Μακεδονίας- Μουσείο Φωτογραφίας Θεσσαλονίκης, Θεσσαλονίκη, 2018.

Sciabarra, Matthew C., “Rand, Rush and Rock”, The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, vol.4, No1, Penn State University Press, pp. 161-185, 2002

Veblen, Thorsten, Conspicuous Consumption: unproductive consumption of goods is honourable, Penguin Books, London, 2005.a